2019/11/24

2019/11/03

English

Saturday 2nd November 2019:

I never learnt Luxembourgish in school because it was not officially considered an important literary language at the time. We learned to read and write first in German, then in French, the latter being the main official language in this country. I didn’t know any English until I was about 15, when my younger brother, who had started learning it earlier, persuaded me that it was a useful and interesting language. I began to take an English evening course offered by our hometown for a small fee — just an hour or so a week.

The following year, when I was 16, I switched schools and started studying English more seriously – a few hours a week. I liked it because it seemed relatively easy as it had a lot in common with German and French, and also with Luxembourgish, and in my view it was somehow more logical, more compact and more direct than those languages.

My parents knew hardly any English at all. Only my mother had learned some in school but never used it.

Most of what I wrote in my teenage years was in German, which is closest to my native Luxembourgish. While I thought I could write well in German I gradually came to feel that writing in English gave me more satisfaction even though it was harder. In later years I wrote in German, and occasionally in French, only when I corresponded from abroad with my parents and siblings, or some friends who didn’t know English.

Since the mid-1970s the vast majority of all I have written, perhaps over 90 percent, is in English.

When I joined the editorial staff of the just-founded New York City daily newspaper The News World at the end of 1976 I got my first chance to write articles in English for publication. My very first story appeared in the newspaper in March 1977.

Of all the editorial staff of the paper I was most likely the least educated, as I had never finished any schools except elementary. So it was a matter of great pride to me when my editors accepted my articles and then made fewer and fewer changes in them as my English improved.

I learned a few words in other languages during my time in the Eastern Mediterranean, the Middle East and the Far East. Today I can still count in Arabic, Greek and Japanese but I cannot converse in those languages. I made rather half-hearted attempts to learn Greek and Japanese on my own but gave up when I felt they were too difficult and not really worth-while for me to know.

One reason I felt this way was that I believed I still had a lot of work to do improving my English, which had by then become my bread and butter. I still believe this, and I find new or forgotten English words in my reading and in my dictionary almost every day.

2019/10/07

On my first Far East trip and on God

At Si Khiu refugee camp, Thailand, December 1979 with Japanese doctors and nurses

Diary Sunday 6 October 2019:

Forty years ago today (6 October 1979) I set off on my first journey to the Far East.

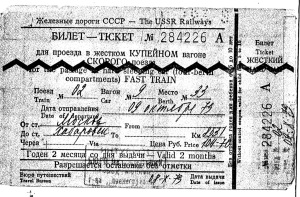

The trip, lasting about 4 months, took me by train from Luxembourg (where I had returned from New York just 3 months earlier after 52 months – 4 years 4 months in the USA) to Liège, Belgium, then to Moscow in what was then the USSR, – Soviet Union – then from Moscow across southern Siberia to Nakhodka on the Soviet Far East coast, then from Nakhodka on a Soviet passenger ship [SS Baikal] to Japan through the remnant of Supertyphoon Tip in the Pacific, to Yokohama, Tokyo, Kyoto, Nara, Itoh (on Izu Peninsula) and Chiba for 2 weeks, then on an Air India Boeing 707 through stormy weather via Hong Kong (Kaitak Airport) to Bangkok (Don Muang Airport), my final destination.

The train and boat rides across Siberia, the Sea of Japan, Tsugaru Strait (between Honshu and Hokkaido) and down the Pacific side of Honshu through very heavy seas to Yokohama took exactly 14 days — 2 full weeks.

In Thailand I traveled twice to Si Khiu near Nakhon Ratchasima to bring supplies to a refugee camp, also visited Thonburi across the river from Bangkok and Bang Pa In just north of the city, and went twice by bus and train for a few days to Georgetown on Penang Island, Malaysia to renew my Thai stay permit. I did not have enough money for tourism there.

After about 3 months I was invited to return to my work in New York (for The News World daily newspaper), and since I was fed up with Bangkok anyway I gladly accepted. At the beginning of February 1980 I flew in a TAROM (Romania) Airlines Boeing 707 via Abu Dhabi or Dubai or Manama (Bahrain — I forget which of the three) to Bucharest Otopeni Airport and then on a Tupolev 154 to Frankfurt, and from there by train to Luxembourg, where I stayed about 2 weeks before traveling by car to England, London, Nottingham and Mansfield for a few days, and flying from London directly back to New York.

It was a very memorable journey, and I was most impressed with Japan.

————–

On God:

Not long ago I went to an African evangelical Christian service and was struck by how much the believers there praised God. To most religious people, especially those of the monotheistic faiths, this would seem quite normal. Many seem to believe that our lives here on earth and in the hereafter have meaning only insofar as we can serve and glorify God. From my experiences with Muslims and Christians, and Jews to a lesser extent, I know that praising God and thanking Him (/Her…) for our existence and for saving us or at least offering us salvation is one of the most important elements of worship (this term itself says it all).

The implication is that we live at His pleasure and have to offer Him devotion and praise. This is the most extreme in Islam, where God’s name is invoked for just about anything, as if believers had to be afraid to be punished for not praising God enough.

I have often wondered what this reveals about the personality, the psychology of the postulated and adulated God. Why would God, who is supposedly almighty, all-knowing and eternal, need to receive so much praise and glorification? Doesn’t that seem extremely narcissistic?

In Sun Myung Moon’s Unification Church we believed that God was suffering, grieving for fallen humankind, which was mostly in thrall to His adversary Satan — whom God Himself also originally created as a good angel, Lucifer. We believed God could not interfere directly with humankind’s responsibility to recognize our fault and return to Him. This was because God had to follow the Principles which He Himself had laid down in creating the Universe and us.

But we also believed God was ultimately almighty and would certainly succeed in His effort to bring humanity back. His will to do that was paramount and unchanging. This was because we were to be God’s children, whom He originally created for love, a love that is supposedly the greatest force in the Universe.

So if we wanted to return to God we had to repent and do penance (pay indemnity as we called it in the church), and to love God by doing His will. God was our original parent, we believed, and He created the Universe for us. But this God was not only a pitiful suffering God. He was also an angry, even vengeful God, as Rev. Moon implied many times in his speeches to us members of his church, and as is told in many passages of the Bible and the Qur’an as well as in some of Jesus’ parables.

God was suffering because we had fallen away from Him and spurned His love, and we continued to either ignore or oppose His efforts to win us back. And we had to pay a ransom to this imaginary Satan, and repent in order to alleviate God’s anger (I think this is the underlying reason for the need of repentance).

Over time all these ideas lost every vestige of sense and meaning to me. This God was either a conceited narcissist or a pathetic yet vengeful character whom I simply could not love or praise. Believers of monotheistic faiths could not convince me that there is such a God. I have come to think this God is really a delusion.

We are not children of a God — we are God, in a way. We are infinitesimally tiny parts of God, yet God develops and changes through us. As individuals we are just sparks in time that leave a residue in God’s Universal Memory when we fade away. But as humankind we represent a substantial part of God.

***

2019/09/19

Thoughts on the 18th anniversary of 9/11, and more…

One of my early articles in The News World under my pseudonym Aaron Stevenson

Diary Thursday 12 September 2019 [continued on 20 September]:

Yesterday was the 18th anniversary of the attack on the World Trade Center in New York City, when 2 towers and one large building collapsed, killing around 3,000 people. As usual, the anniversary (9/11) was marked around the world with ceremonies in which people expressed their support of the great USA.

I want to take stock of my feelings for that USA, which I long regarded as a second homeland.

My father always professed to hate the USA — though by no means all of her people or even the culture. He watched plenty of American movies, for example. He used to say the US were dominated by “Jews,” who were an ethnocentric tribe of money-grubbing Shylocks, in his mind.

His view of “Jews” was colored by his involvement with Nazis in World War II, when he was a mechanic in the German Air Force, the Luftwaffe, in which he had enlisted because he loved airplanes and had hopes of becoming a fighter pilot [he was not accepted for that special training as he was past their age limit of 28 at the time].

I don’t think he ever knew any real Jews. They were mostly just caricatures in his mind, I think. So, to him they were all one kind, all the same, with the same Shylock-type attitude.

I don’t know now if my father’s feelings about the Jews and the USA influenced us his 6 children in any way. Perhaps the only one really affected by this is my brother Gilbert — but in an opposite way. Among all of us Gilbert was the one most in opposition to my father’s ideas and visceral impulses. So Gilbert has become a very ardent supporter of the USA and Israel, and the Jewish people in general — whom he almost completely identifies with Zionism.

So what about me? I don’t think my father’s expressed feelings about the USA and the “Jews” affected me very much. Like most kids my age I was fascinated by many aspects of American culture and by the USA as a whole.

The assassination of President Kennedy and the mystery surrounding it affected me, though. I was close to 13 years old (12 y. 9 mo.) when it happened in November 1963 (actually, the day before Gilbert’s 11th birthday). I remember staring at the large black and white pictures in the German magazine “Stern,” which my father used to read. I found it hard to believe that Lee Harvey Oswald was shot dead by Ruby right after he was nabbed by the police. Somehow the assassination itself and the aftermath, followed a few years later by the murders of Martin Luther King and Kennedy’s brother Robert, seemed totally sinister, evil — and in my mind a cloud descended on the rosy image I had of the USA.

When I saw pictures and film of what the US were doing in Vietnam I even joined a protest march to the American Embassy in Luxembourg City once; I think that was in the winter of 1968-69. However, this did not mean I hated the American people or the culture. Around the same time I met Ben Barker in Clervaux (Luxembourg), my first American friend. He was a middle-aged itinerant evangelical preacher and puppeteer, on a bicycle tour of Europe. We corresponded for a few years after that, though I never saw him again.

In school, where I started learning English from the age of 16 (February 1967 — in the Lycée de Garçons/Esch-Alzette), I tried to speak the language with what I thought was an American accent — to the displeasure of my teacher, who spoke the purest Oxford English.

Also, in 1968 or 1969, I applied for a scholarship offered by the American Field Service that would have allowed me to study for one year at a high school in the USA. I wrote an essay for them — I think it was about American-Luxembourg relations — and was accepted. The only problem was that my parents had to pay for my air ticket to the US and give me some money for expenses, as I did not have any except in a special savings account that could not be debited until I was 21 (1972) [I had already earned a small salary in 1966-67 when I worked as an apprentice fitter in the ARBED Belval steel mill for about 6 months — but that money mostly went into the savings account]. My parents could not afford to pay, so I had to cancel my application for the AFS scholarship.

By 1972 I was desperate to get away from Luxembourg, so I got my first visa for the USA from the same Embassy I had marched against a few years earlier. In my correspondence with my friend Ben Barker during those years I had learned quite a bit about America but we had a mild dispute about the US bombing of North Vietnam, which he supported but I abhorred. He wrote from different places as he moved often — from Maryland, Virginia, Rhode Island, etc. He always wanted me to read the Bible and accept Jesus as my personal Savior. I still have 5 of the letters Ben wrote me, from 1969 and 1970.

In 1972 I also went to Brussels to visit the Canadian and South African Embassies and to ask what I needed to do to immigrate to either of those countries. The Canadians said I first had to find a job in Canada, and for the South Africans it was more or less the same — though they told me my qualifications were insufficient.

Between 1975 and 1982 I spent a total of just over 6 years in the USA, mostly working with the Unification Movement (Korea’s Sun Myung Moon) and its offshoot companies, especially the daily newspaper The News World in New York City, which we launched at the end of 1976.

I never returned to the US after 1982 but worked for ABMC, a US Government agency, from 1992 until my retirement in 2016. ABMC (American Battle Monuments Commission) maintains the (WWII) Luxembourg American Cemetery where I was custodian-guide and associate those 24 years.

In my time in the US and later in the cemetery I got to know many Americans and learned a lot more about the USA.

In the Unification (“Moon”) Movement in America we were very patriotic, very positive about the country and its role in the world. This was, of course, reflected in our newspaper. I edited and wrote many articles with a strong pro-American, conservative bias in those days, because like most “Moonies” I believed the US was the most important country, without which the world could not be saved from evil communism and socialism.

I shook off the unease and even horror I had felt earlier about what the US had done to Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. The USA had withdrawn from that region and now those countries had fallen to communism.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s I had been curious about the Soviet Union, and my father always viewed the Russians positively as a counterweight to the USA. I sometimes read a pro-Soviet magazine in German, Sowjetunion Heute, and found it quite interesting although I was not attracted to Russia nearly as much as I was to the USA. At one point in 1971 I visited the Soviet (USSR) Embassy in Luxembourg-Beggen to sign a book of condolences for the 3 cosmonauts killed in space during the Soyuz-11 mission. I received a free lifetime subscription to Sowjetunion Heute, which my father went on to keep after I left Luxembourg.

In October 1979 I crossed the Soviet Union by train on my way to Japan. The country appeared rather shabby to me, almost like a Third World nation, not at all like a great superpower that threatened the west. A few months later when I was living in Bangkok I heard and read about the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan (a country I had visited in March 1972 on a very memorable trip). I was shocked. I hadn’t followed events leading up to the invasion — at least not closely. In the newspaper in New York during 1978 and 1979 the Iranian Revolution dominated the headlines and our attention. Afghanistan seemed a sideshow. Now the Soviets, the “evil communist empire,” had broken out of their underbelly and seemed poised to march to the shores of the Arabian Sea.

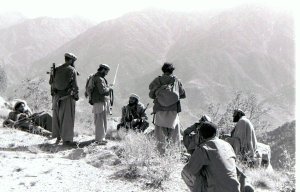

Later, during the 1980s when I worked for the Middle East Times, I wrote many articles about Afghanistan and traveled to some of its eastern border areas three times with mujehideen from Pakistan. All 3 times I came under artillery fire from Afghan and Soviet forces. My articles were, of course, biased against the Soviets and their Afghan allies/”puppets.” I was still very pro-American, keeping the mindset I had acquired during my time in the USA.

Yet I began to have some doubts. Actually it had already started when I was still in New York working for The News World. The first stirring of my doubts about what we were doing began when I was asked to write our top story of the day, under a banner headline, hailing the military coup d’état in La Paz / Bolivia led by General Luis Garcia Meza Tejada in July 1980.

At the time our company published a right-leaning, anti-communist Spanish newspaper, Noticias Del Mundo, whose offices were located one floor above our newsroom in our building — the former headquarters (until ca. 1940) of the famous Tiffany & Co., at 401 Fifth Avenue (37th Street entrance).

The editor-in-chief of Noticias Del Mundo was an Argentinian journalist named Rodriguez Carmona, who I believe had ties to his country’s intelligence service under the bloodthirsty dictatorship of Gen. Jorge Videla. Rodriguez Carmona provided the information based on which I was to write my article. I was reluctant because I had doubts about the character of the coup plotters in Bolivia. In the end I wrote the story as suggested by my editor, Robert Morton, and it was published at the top of our front page under my pseudonym byline (in the paper, whenever I was in New York City, I always wrote under the name Aaron Stevenson, which was chosen for me in early 1977 when my first story appeared, due to concerns about my status as an illegal alien; when I worked for the paper out of Washington DC in June 1979, for some reason, my real name Erwin Franzen was used with my stories).

I was not happy about that story on the coup and it became one of the reasons I quit my job temporarily a month later (late August 1980) and returned to Luxembourg for 4 months until I got fed up there again and came back to New York and The News World at the beginning of 1981.

Bo Hi Pak, our publisher and our founder Rev. Sun Myung Moon’s interpreter, and my editor Morton and most of our staff welcomed the Garcia Meza coup because it kept Hernan Siles Zuazo from gaining power as he would have in fair elections. We regarded Siles Zuazo as a dangerous leftist. Pak and some of our members went to Bolivia and were well received by the coup leaders. They were enthusiastic about the prospect of being allowed and even encouraged to teach Victory Over Communism (our anti-communist doctrine) in schools there and to establish chapters of CAUSA International — our church’s new anti-communist political organization, which focused mainly on Latin America and Hispanics in the USA.

From the beginning it was clear that the Bolivian coup was backed by Videla’s dictatorship in Argentina, and some of our people were happy about that because they were regarded as staunch anti-communists.

Soon, however, it also became clear that those nice, friendly anti-communists were torturing and massacring opponents and even anyone who could be labeled a leftist or human rights activist. The coup leaders also enjoyed active support from some Nazis such as Klaus Barbie, the “butcher of Lyon” in World War II, who was responsible for the murder of thousands of Jews.

Garcia Meza and his henchmen were also deeply involved in cocaine trafficking. When Ronald Reagan became President early in 1981 his administration learned from the FBI about the Garcia Meza regime’s involvement in drug trafficking, and quickly began to distance itself from them. Articles about this drug business appeared in American newspapers, and soon La Paz became isolated.

We also ended up having to distance ourselves from them. But the episode taught me that our stance of almost blindly supporting anyone who professed anti-communism was at least very naive if not outright dangerous.

I began to have doubts about US support for dictatorships like that of Pinochet in Chile and Videla in Argentina. Jimmy Carter had emphasized human rights and tried to push some US allies to improve their record in that area. Under Reagan, however, human rights violators were only criticized and punished if they were leftist or communist, or did not submit to US pressure. Our members whole-heartedly agreed with this idea, and I tend to believe a majority of them still do even to this day.

CONTINUED on Friday 20 September 2019:

During the 1990s I was somewhat ambivalent about America’s role in the world. The Soviet Union had collapsed and it seemed the US now regarded itself as the ultimate power in the world. A first glimpse of this emerging reality was, in my view, afforded by the 1991 Gulf War.

While it is true that the GHW Bush administration consulted with Soviet leader Gorbachev at the time, it was clear the US was in the driver’s seat. There was already no doubt in anyone’s mind that the USSR was crumbling, dying. And China was still mostly a Third World country, though, like India, equipped with some nuclear arms.

I certainly didn’t like Saddam Hussein but I felt the crisis in the Gulf when he invaded Kuwait should be resolved by diplomacy, not war. When the US built a coalition of military forces to attack Iraq I did not like it because I felt it was not necessary and could lead to great disaster. I remember Bush sought advice and support from evangelist Billy Graham before he launched the assault. I did not like that at all. It seemed like a Christian leader gave his blessing to a war of choice, not a defense of the United States. The US was not threatened by Iraq, and everybody knew that country would not stand a chance fighting America — with or without a coalition of other powers.

Then the inevitable happened. Iraq was devastated, leading to vastly more death and destruction than it caused in invading Kuwait. Then there was the so-called “highway of death,” what US airmen called a “Turkey shoot.” American bombers totally butchered hundreds or thousands of Iraqi soldiers who were retreating from Kuwait. That was absolute, wanton mass murder and a war crime in my book. Yet I gave the United States the benefit of the doubt.

It took many more years before I finally changed my mind. When Clinton later bombed Serbia in 1999 I thought he and NATO were fully justified because of what I had heard and read about what the Serbs had allegedly done to Bosnia and Kosovo. I would change my mind about that only much later when I learned more about what happened from non-western points of view.

In the cemetery where I worked we always held ceremonies to mark Memorial Day and Veterans Day, and often on other occasions as well, such as the anniversary of the liberation of Luxembourg (10 Sep. 1944) and the start of the Battle of the Bulge (16 Dec. 1944). We always had American general officers or top diplomats speaking at these events. Invariably they would equate what American military forces were doing around the world at this time with what the GIs did in World War II — defending the US and Europe against the forces of evil.

They also always portrayed the deceased soldiers as heroes who died on the battlefield for a great cause. One word that I missed in most of their speeches was peace. I also missed it in our agency ABMC’s publications and in the instructions given us for guided tours of the cemetery. Our motto became: “Time will not dim the glory of their deeds,” taken from a statement by Gen. John Pershing, the founder. The emphasis was always on “glory.” The soldiers rested “in honored glory.” Their deeds in war were “glorious.” So that meant in a way war was good, because it brought glory to those who won, who defeated their enemies, anyway.

But I took very many family members and close friends or war comrades to the graves of their loved and cherished ones over the years. The family members and buddies clearly felt sorrow over the loss of those young men (and one woman, among over 5,000 dead), not glory. They did not say they were happy that their loved ones rested in “glory.” I think they mostly wished for peace, that almost forbidden word / idea. Most said they hoped there would never be another war like World War II, no conflict in Europe or — God forbid — in America.

I felt there was a major change after 9/11, a hardening of the attitudes of many Americans towards people of other cultures such as Muslims. There was also a big change in our agency, ABMC. Whereas in the 1990s we had struggled financially and our mission was not considered especially important, after 2001 the US Congress greatly increased our budget, and our work was given a major impetus. But the idea of peace was buried ever so deep, it seems to me. America was at war and had to continue in this state indefinitely. So those who had fought in the world wars of the 20th century were honored even more than before, because they had made America not only great but the greatest of all the major powers of history.

I read several books and a lot of articles on the Internet that gave me insight into unsavory aspects of American history, and foreign and military policy, of which I had hitherto known very little. In recent years I have become almost totally disillusioned with the USA as I have observed how they strive to put a stranglehold on the whole planet with their enormous military and economic power and their gigantic intelligence apparatus, which they use to destroy, to coerce, to lie and to cheat others.

In my opinion the US use by far the largest proportion of their power and their wealth to dominate or crush other countries, and only a comparatively puny share to help and support those in need. I believe Russia and China and Iran, and other potential rivals or foes of the US build up their own military forces and intelligence capabilities as much as they do because they feel rightfully threatened by the US.

2019/03/05

Escape from God …?

Excerpts adapted from recent diary entries (important clarification inserted in bold below on 13 April 2019):

On the Run from God… (provisional title of the memoirs I am writing).

My grandmother used to tell a story about me when I stayed with her once as a very small boy. She said I had been outside their house in the sun for a short while one day when I suddenly came running inside exclaiming: “The sun is moving! The sun is moving!”

When she and my grandfather looked at me I said I saw how the shadows of the houses moved.

My grandmother, who was a good Catholic, said: “The sun does not move but God holds our earth in his hand and moves it around the sun.”

“Can we see how God does this?” I asked, and she told me God cannot be seen.

Then, according to her story, I retorted: “How can God move our earth if we cannot see him? I cannot believe this.”

For some reason my answer impressed my grandmother so much that she regarded me as a very bright kid.

Perhaps ever since that time I have tried to find this invisible God.

I was raised a Catholic and took my religion seriously until doubts became too strong in my teenage years.

In my early twenties while traveling in the Middle East I officially became a Muslim in Damascus, Syria and performed the Haj (pilgrimage) to Mecca and Medina with some friends. Having forsaken Catholicism I was yet unable to become inspired by Islam and never delved into it.

Then two years later, at age 24, I met the Unification Church of the Korean Rev. Sun Myung Moon in the United States. I became more inspired than I had ever been before and thought I had really, finally, found God.

The Divine Principle, the teaching of Rev. Moon, and the mostly friendly and loving yet also very competent members of this movement convinced me for a time that God worked through them to create a better world. I always had doubts, of course, about God, about Moon, about the teachings and also about my fellow acolytes. But I felt nonetheless that this movement was the best hope for a humankind I considered debauched and bound for self-destruction.

…. About the title of my book “On the Run from God”: the God from whom I am running away, trying to escape, is a myth – in my view. It is an extremely powerful myth that holds most of humankind in thrall, in bondage. To me it is a God that cannot exist but is nonetheless real to most of my fellow humans.

…. I don’t believe in such a God. I thought I did many years ago, and clung to an illusion of such a belief for many years. But gradually, between 1994 and 1998, I came to realize that my belief itself was unreal – it wasn’t me. I did not really, deeply believe in such a God. I never did. I only wanted such a God to exist, because I accepted other people’s contention that it was good, right, just.

Starting in 1994 I applied Occam’s Razor to the entire concept of that God. Over the next several years I came to understand that I could never really believe in such a God and that such a God really could not exist. It did not make any sense at all anymore.

Today I remember that it was comforting to believe there was an almighty father/mother who had created us and who was good, benevolent, gracious, compassionate, and who always supported us when we did our best to be good too.

It was comforting to feel we were the children of this God, and that together with our Heavenly Father/Mother we could right this world, rid it of all evil. I, too, clung to this belief. I always had doubts, which I had to find ways to overcome. I imagine everybody wrestles with such doubts at times.

Then we have to dig deep into ourselves and pray, and our hearts tell us how bleak and terrible the world would be without such a God. And we repent. Then we feel good. We feel this God’s warm embrace. It seems God likes it most when we repent. That is what binds us to this God – repentance. And it always makes us come back for more of this warm embrace that we feel after we repent. I felt like that too, many, many times.

However, this warm embrace is gone when I return to reality, when the prayer is over. Very quickly afterwards there is nothing left but a memory of the embrace that fades fast when confronted by the reality around me and the realization that nothing has changed as a result of the prayer. Everything is still broken, shattered. The world is still beautiful in one sense and a horrible mess in another.

I do believe it is up to us to right this world. I do believe I should do my best to be good and do good. Simply because I am horrified by the bad I see within myself and around me, and because I love the beauty and the goodness that I also see everywhere.

In my view now there is a real God hidden behind the mythical, false God described by the monotheistic religions. The real God must have inspired the myth but is quite different from the way He/She/It is described. Over the last 20+ years I have been trying to understand that real God, and I am still searching….

I believe I, we, all, everything, are parts of this real God. God is all there is. God, originally, is not good or bad. Yet He/She/It encompasses all the good and all the bad, all the beauty and all the ugliness as we understand them.

God as universal consciousness divided Him/Her/Itself into innumerable parts, each clinging to a physical entity – a projection that made the separation from other parts of universal consciousness real. Many parts were joined together in larger physical entities. Each of us humans is composed of many parts joined together. Our individual consciousness arises out of the many parts joined together to form one mind and one body.

Our individual, separate consciousness cannot continue to function once the body that holds it decays. It’s like water in a cup. When the cup breaks the water flows in all directions until eventually it returns to the ocean. The ocean is universal consciousness, God. But the water has memory. There is universal memory, which in my mind determines time itself. There is also entropy, which I think degrades the memory to some extent. I don’t know, of course. These are just stray thoughts of mine.

God created everything by dividing Him/Her/Itself and then pushing everything to evolve in various directions. I believe we humans, collectively, are a spearhead of this evolution of God. There may very well be others, other spearheads – meaning the most highly developed, separate forms of consciousness. This evolution continues, of course. God’s – and our – understanding of good and bad evolved from the interaction of the separate consciousnesses into which God had divided Itself, especially us humans (spearhead/s).

I believe God, as the sum or the ocean of universal consciousness, retains an identity, a personality clinging to the physical universe as a whole and in particular to the spearhead/s of evolution (really God’s own evolution) – us humans (and perhaps other such spearheads – advance guards – in other parts of the universe). So this God inspired all the so-called holy scriptures (at least those who conceived them) and prophets, etc. God inspired those who produced what became the Torah, the Bible, the Vedas, the Avesta, the Quran and many others. But God’s own personality evolved and continues to evolve – through the spearhead/s, through us.

That is my belief now, after struggling for many years to formulate an understanding that would explain my doubts and allow me to separate from the teachings of Rev. Moon to which I had clung almost desperately for so long.

2018/03/03

My current idea of God in a nutshell

I believe God is everything and everything is God. God is universal consciousness, universal memory.

We humans, collectively, are a spearhead of the evolution of universal consciousness, and each one of us is a facet of God’s character. There may or may not be other such spearheads in other parts of the universe.

Time is the accumulation of memories in universal consciousness. Time appears to flow in one direction because memories cannot be erased from universal consciousness.

I do not believe we as individual human beings are eternal in any way except that we continue existing as memories in universal consciousness. Upon final separation from our physical bodies our individual spirit or consciousness dissolves back into the whole from which it came and of which it always remained a part.

It can be said that God grows through us, changes and learns through us — until we may be superseded by a higher intelligence. God is not good or evil in itself but through us God is both. God cannot change our world except through us…

2018/02/09

How I met the Unification Movement — part 1

INTRODUCTION

Like many people throughout history I have been on a quest: a search for an understanding of ultimate reality. This has been the fundamental theme of my life. After a long, meandering journey I have found an explanation that satisfies me but is difficult to use as a guide in my life. Along the way I have come across some other philosophies of life and learned very much from them. One in particular served me as a guide for many years and set my life on a course which I can and will no longer change: the Divine Principle as taught by the late Korean religious leader Rev. Sun Myung Moon.

I no longer believe in the Divine Principle and Rev. Moon, who proclaimed himself with his wife Hak Ja Han as the “True Parents” of humankind, essentially the one and only Messiah. In fact I no longer believe even in the God postulated by the monotheistic religions. My idea of “God” is quite different, closer to the reality I perceive and understand. But I am no longer alone and free to pursue my quest wherever it may lead me. I have a family and a responsibility that I cannot and will not shirk. My family was begun by Rev. Moon and is inseparable from him and the movement he founded.

Here, then, is the story of my meanders.

——————————————–

Chapter 1

New York City, Thursday, 6 March 1975. After a long flight over the icy wastes of Iceland and Labrador, this was Manhattan, a different world. It was after dark, on 42nd Street near Grand Central station, when I encountered what to me was a foreboding of Doomsday. The tall, dark buildings, the impression of decay given by the city’s famous potholes, and the steam rising here and there from pipes running under the streets reminded me of a haunting image I had in my mind of the aftermath of a nuclear holocaust, which I expected to occur within a few years’ time.

It was a relatively warm night for this time of the year in New York. As I walked with my backpack on my back, I noticed a young man standing on the sidewalk in front of a small blackboard, alternately drawing and gesticulating rather wildly while he gave what seemed to be a lecture at the top of his voice. The funny thing was, there was no one listening.

Another young man stood a few meters away, apparently waiting for something or somebody, but he seemed to pay no attention to the first one. I looked at the blackboard but the figures the lecturer had drawn meant nothing to me. I caught the words “Last Days” in the stream of his talk, and then something about the Bible and a “Divine Principle.”

Tired as I was after the long flight, the man’s lecture seemed too arcane for me to be able to figure out what he was talking about even though his mention of the “Last Days” had intrigued me. Also, I was hoping to catch a train to Montreal rather than having to spend the night in New York. So I asked the bystander where I could find out about trains to Canada. “Sorry mate, I can’t help you there,” he said with an accent that didn’t sound American. He turned out to be an Australian who knew little more about New York than I did.

As I walked on, down Park Avenue, then over to Fifth Avenue and back up towards 42nd Street, I saw more young people giving lectures in front of blackboards set up on the sidewalks. Some of them had an audience, others did not. They all seemed to preach the same message and draw the same figures.

One of the city’s yellowcabs stopped at the curb in front of me and two well-dressed young women got out, one black, the other oriental. Both came right up to me and introduced themselves: Barbara from Guyana and Tamie from Japan. They asked me if I needed some help. I told them I was from Luxembourg and asked where I could catch a train to Montreal. Barbara said I had to go to “Penn Station” below Madison Square Garden. She told me they would take me there but could not because they had an appointment in the building in front of which we were standing.

She explained that they had to attend an important lecture about a new revelation about God and a new understanding of the Bible, and she invited me to attend if I was interested. I said I might be interested but first I had to find out about trains to Montreal, as I was hoping to catch one that same night. Barbara gave me directions to Madison Square Garden and both girls handed me their business cards, suggesting that I call them if I needed any further help.

I walked slowly down Fifth Avenue, lost in thought. Yes, this big city really conjured up the feeling that it was doomed, and the entire civilization that created it was doomed. It would all be annihilated in the nuclear war that I saw coming within a few years’ time. That holocaust had to happen — and I actually wished for it to occur. Because I felt that something was fundamentally wrong with this civilization. More than that, something, was fundamentally wrong with humankind.

In my view, the earth and in fact the entire universe was a harmonious whole, like a gigantic organism within which every part played a certain role and all parts were complementary to each other. Only man did not fit into this harmonious whole. Man was like a malignant cancer that, though originating from the whole, spread uncontrollably and destroyed other parts of the organism. Man alone was going against the purpose and design of the universe, and modern human civilization represented a cancer that had grown to such proportions that it threatened to overwhelm an entire planet. It had to be destroyed. Actually, because of its inherent contradictions, it was bound to destroy itself.

But I believed there could be, there had to be, a new beginning — because the universe had brought forth humankind and it was thus meant to exist, but it clearly had somehow gone wrong. Modern civilization would be destroyed but there would be survivors in different places. Those people would have to live in nature and start anew, but they would have to avoid the original mistake that made man go in the wrong direction.

I felt that those survivors had to become completely one with nature, one with the spirit of the whole, the essence of the universe. And they should never ask the question “why?” To me, this was the root of all the problems. We had to attune our hearts and minds to the harmonious whole of the universe without ever asking why things were the way they were and why we were what we were. Asking “why?” somehow meant that we separated ourselves mentally from the whole — and that was what caused humankind to go astray.

Our ancestors in Stone Age had made this mistake, and the survivors of the expected nuclear holocaust would have to go back to Stone Age to try again. I was on my way to Stone Age. I was planning to go to a remote area in the wilds of British Columbia and to try to live in nature on my own, ridding myself gradually of all the implements of civilization that I carried with me to help me get over the initial shock.

I felt that if I could survive like this for a year or so, then I was ready to become one of the survivors of the nuclear war to come — and perhaps even a leader of a new humankind. I was 24 years old and I believed the nuclear war would come in 1979, which was four years away. After spending at least a year in British Columbia, I wanted to make my way down to Patagonia, where I would wait for the holocaust to begin. The reason why I had chosen Patagonia was that I felt there would be less nuclear fallout over the southern hemisphere because most worth-while targets for nuclear strikes were in the north.

In front of Madison Square Garden I saw two blackboards like the ones I had encountered before. Several people were standing around either listening to two preachers who were lecturing about the Last Days or talking to others.

I watched the scene for a moment and then looked for the passage to the train station below the building. Just as I started moving toward the entrance an Oriental lady in her 30s approached me and asked if I was interested in science or religion. I said I was interested in both. She gave me a flyer and told me the people lecturing about the Last Days were speaking about a new revelation that could bring science and religion together for the sake of world peace.

The idea sounded good to me, and when she told me a little more about it I realized it must be the same revelation the Guyanese lady Barbara had mentioned a little earlier. I asked where she was from and it turned out she was Japanese, and her name was Noriko. I gave her my name and told her I had just arrived from my country Luxembourg but wanted to take a train to Montreal that evening or early next morning.

She said she hoped I could find the time to listen to a special lecture about the new revelation, which she called the Divine Principle, before I took off for Montreal. The lecture was going to be held in a building across Fifth Avenue from the New York Public Library, exactly the place where I had met Barbara and Tamie earlier.

I said I was interested but I needed to get information about trains to Montreal and to buy a ticket first. Noriko called a tall young man standing nearby and asked him if he could show me where to find what I wanted. The man introduced himself as Bill. He took me down to Penn Station, where I bought a train ticket to Montreal.

A little later Bill disappeared briefly and then returned driving a big Dodge van. Noriko and I got in and we drove to the building near the library on 5th Avenue, picking up a few other people along the way.

I don’t remember any detail but we entered a hall full of people, with a man in front who had just begun to give a lecture. From time to time he drew figures and symbols on a large board facing the crowd.

He explained about how God’s nature is reflected in everything through the dualities of internal character and external form, and positive and negative charges or male and female genders.

He said God was like a parent to us humans, whom He created in order to share his love. But, as told in the Bible, when the first humans fell away from their Parent He had to let them go their own way because He did not want to interfere with their freedom of choice. In order to win them back to His side He guided leaders He chose among them to set conditions that would ultimately prepare the way for a Messiah, a person who perfectly embodied God’s love.

This Messiah would have to find a perfect bride together with whom he would become the “True Parents” in reflection of God’s dual nature and lead humankind back to Him. The Messiah was Jesus Christ, but the people did not follow him, so he could not find a bride and had to sacrifice his life to become a spiritual guide and inspiration to the world.

Jesus’s followers the Christians then became the people through whom God worked to fulfill His providence to bring a Messiah who could become the “True Parents” of humankind. The Last Days prophesied in the Bible was the time when a new Messiah would appear with a new understanding of God’s truth, and this time was upon us. ….

I remember seeing many pictures on the walls of the man I later learned was Rev. Sun Myung Moon of Korea, the man who had discovered the Divine Principle, and I couldn’t help feeling even then that perhaps he was the one the people here believed to be the new messiah.

At the end of the lecture the speaker suggested there was much more to the Divine Principle than what he had just explained. He invited anyone interested in learning more about it to attend a weekend workshop in a beautiful place in the countryside on the Hudson River north of New York City.

Over snacks and drinks after the talk Noriko introduced me to a few of her friends who were all members of the Unification Church, the movement founded by Rev. Moon. Some of them asked me how I liked the ideas presented by the speaker, whom they named Mr. Barry. I said I thought they were quite interesting because they seemed to indicate a possibility to reconcile the Bible with modern science. Also, I liked the proposition that Jesus’ death on the cross was not God’s original plan.

When Noriko suggested I attend the workshop Barry had mentioned I told her there was a problem: I was allowed to stay in the United States only until the next day, 7th March. This was because the immigration official at J.F. Kennedy Airport who checked my papers stamped that date on the I-94 card that he stapled into my passport. He had asked me how long I was planning to stay in the US and I said I wanted to take a train to Canada either that evening or the following day.

When I showed her the form in my passport Noriko went to talk to Barry and others about it. Barry later came up to me and said my stay permit could easily be extended. He seemed quite confident about it, so I decided there was no need to worry and I could spend the next weekend in the retreat upstate on the Hudson, which he had called Barrytown.

I was told a bus would take people to Barrytown the next evening, so I thought I might have to spend that night in a hotel. Barry suggested I could stay in a house owned by the church in Manhattan, on 71st Street.

Late that evening Bill, driving his Dodge van, took Noriko, me and several other people I had met after the lecture to the house Barry had mentioned. The church members called it a “center,” and it seemed packed with mostly young people. The men and women were strictly segregated and lived on separate floors. I was taken to a large room where many men lay close to each other in sleeping bags on the floor. The ceiling lights had already been turned off, so it was fairly dark inside. I found a place in a corner with just enough space for my backpack and sleeping bag.

Early next morning we were all woken up when the lights were turned on, and we had to take turns using the bathroom and the few sinks where we could wash our faces. I talked to some of the men there, and when they found out I was not a member of the church they were surprised I had been allowed to spend the night there with them.

Noriko came to our men’s floor a little later to pick me up for a sightseeing tour of Manhattan. We had lunch in a Japanese restaurant that day and visited Central Park, the Empire State Building and a few other places around town. ….

2014/11/11

About my first journey to Japan, across Siberia, in 1979:

I traveled across the southern part of Siberia on the trans-Siberian train in October 1979 during Soviet times — from Yaroslavski station in Moscow to Khabarovsk, where all foreigners had to get off to spend a night, and then from Khabarovsk to Nakhodka east of Vladivostok. I loved the Lake Baykal area most, where the train passes a stone’s throw from the lake shore near Slyudyanka, with the snow-capped Sayan Mountains on the Mongolian border to the south. Beautiful. (Scroll down to the bottom of this post under the links to “Photos:” for more on my impression of Soviet Russia during that 9-day journey across the vast land).

***

The trans-Siberian was part of my first trip to Japan. It took me exactly two weeks to get from Luxembourg to Yokohama, from 6 to 20 October 1979 — 11 days on trains. I was ushered to Japan on the Soviet Morflot passenger ship Baykal by the remnant of Supertyphoon Tip, which a few days earlier had been the largest and most intense tropical cyclone ever measured (it’s described in Wikipedia and in a 1998 report I have from the US National Oceanicand Atmospheric Administration).

***

We left Nakhodka about midday on 17 October 1979, crossed the Sea of Japan (or Eastern Sea), then passed through Tsugaru Strait between the Japanese islands of Honshu and Hokkaido before turning south off the Pacific side of Honshu, headed for Yokohama. The weather was really beautiful and the sea was calm until some time after we passed Hakodate on Hokkaido Island in the afternoon of 18 October, entering the Pacific Ocean. The sky darkened, the sea got rough — I got seasick fairly quickly — and soon all passengers were asked to go below deck because the ship’s crew was going to lock all hatches. No passenger was allowed on deck any more. The captain’s announcement did not say anything about us heading into a big storm but it was obvious from the rocking and creaking of the boat that something like that was afoot.

***

Not long after that I spent about 24 hours passing back and forth between the bed in my cabin and the toilet across the corridor, my body seemingly turning inside out from extreme seasickness. Around midnight of the 19th the storm eased up, and the Baykal steamed at full speed towards Yokohama Bay, which we finally entered around 6 a.m. on the morning of the 20th. The Baykal’s nice sunroof aft on deck was almost completely chewed up, as if a giant had bitten off pieces of it.

***

A Japanese coastguard or customs boat pulled up alongside and officers came on board the Baykal to check our passports.

When I first got down to the pier at Yokohama I suddenly felt very dizzy and for a moment, inadvertantly, I rocked back and forth to keep my balance as if the ground under my feet was like the boat in the typhoon…

***

About photographs, or lack thereof ….

***

Nowadays I regret very much that it took me very long to realize it would be a good idea to buy a camera and take pictures during my travels. My father always had a camera and took a lot of photos, and he also shot quite a bit of film of our family with a small wind-up 8-mm Yashica camera that he bought at the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958. Despite this it didn’t occur to me that I should get a camera of my own to take along on my travels.

***

I did buy a cheap Polaroid camera shortly after I arrived in New York City in March 1975 and took a few pictures in Central Park that I still have — nothing very interesting. In 1982, again in New York, I took a few more pictures in the Chinatown area with another Polaroid.

***

I finally bought my first 35-mm camera in 1984 during a short trip to Luxembourg to renew my passport while I was living in Cyprus. It was a Yashica, fixed-focus — very simple and cheap. But I took a lot of good pictures with it in Cyprus, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Japan, where I bought an Olympus OM-10 with a 35-70 lens at Camera-No-Doi in Tokyo in 1987. This Olympus served me well in Japan, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Greece, Egypt, Cyprus and Luxembourg, though I never learned how to use all its features. Since 2003 I have been using digital cameras, including a Fujifilm Finepix S2950 that I got for my 60th birthday in early 2011 — nothing fancy but I’m quite happy with it, though still shooting mostly on automatic…..

***

Here are links to my posts on my travels, and to some of my photo albums:

***

My answers to questions about my trips to Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan in the 1970s-1980s

***

Photos:

***

***

————————————–

On my 9 days in Soviet Russia (8-17 October 1979)

From an email to a friend:

About my first trip to Japan, I was not pressed for time and thought it would be more interesting to go by train and boat (rather than flying). Also, I wanted to see with my own eyes what the Soviet Union looked like. At the time, in New York, I worked for a Moonie (=followers of the late Korean Christian sect leader Sun Myung Moon) anti-communist newspaper where all of us regarded the USSR as the big enemy, the ‘evil empire.’ I was on my way via Japan to Bangkok/Thailand, where I wanted to work as correspondent for that newspaper.

At the time also, the leader of our religious movement Sun Myung Moon himself kept saying he wanted to go to Moscow to hold a ‘freedom rally’ in Red Square, and all of us Moonies were supposed to prepare for that (it meant the liberation of the USSR). I was quite skeptical of his chances of doing that but I wanted to get my own impression of the country first.

Well, on the train in West Germany headed for Moscow I met a man who was a Communist Party official from Tselinograd, Khazakh SSR. He spoke German and we talked quite a bit all the way to Moscow, which took 2 days. Later, I corresponded with him for a number of years until his wife wrote back to me one day in 1990 that he had died.

I was surprised to find that the undercarriage of the whole train had to be changed at Brest on the Polish-Soviet border, a process that took a couple of hours. It was, of course, because the rail gauge is different – wider – on the Soviet side.

I thought, well, if the Soviets launched a major offensive against western Europe, as us anti-communists feared, they would face a problem bringing enough supplies from the hinterland to their troops on the front line if every train from their country was held up at Brest and other places like that. They would represent bottlenecks. Road and air transport wouldn’t be enough for the logistical job required. Also, those places would make valuable targets for air strikes from the west.

I didn’t see how the wheels were changed because a Soviet border guard took me off the train when he found a book (supposedly) of Khrushchev’s memoirs in English in my luggage. I was kept waiting for awhile in an office at the border and was asked to sign a paper agreeing that I could not take that book into the USSR and in effect allowing them to confiscate it. They asked a few questions but were generally polite. I actually had a lot of other stuff in my luggage that I had reason to be more worried about than that book, but they didn’t check very thoroughly at all.

In Moscow I once walked into a sort of cafeteria for local workers, listened closely to how the other customers ordered bread, sausage and beer in Russian, and ordered the same in Russian (at the time I still ate meat). I didn’t feel that anybody noticed I was a foreigner.

The country looked poor and generally quite shabby to me, not at all like a great superpower. There were other incidents during the trip and especially in Khabarovsk where I did things normally forbidden but nothing happened and I didn’t have the impression that I was being watched very closely. Near Novosibirsk I saw roughly 3 dozen armored personnel carriers on a train in a shunting yard, and when I heard a few months later in Bangkok that the Soviets had just invaded Afghanistan I thought those vehicles I had seen in Siberia might have belonged to a contingent getting ready to move down to Uzbekistan in preparation for the invasion.

A few years later, of course, I would come under artillery, mortar, tank and rocket fire from some of those Soviet forces and their Afghan allies in Afghanistan myself – and see a lot of destroyed Soviet APCs, tanks, field guns, etc. – and also many dud bombs lying around (yes, many failed to explode, probably because of the negligence [or even deliberate sabotage] of disgruntled workers in Soviet munitions and other factories, producing mostly shoddy goods).

Really, no, to me the Soviet Union didn’t look like a big military power threatening the west, though it took some time for that realization to sink in.

Already at the end of 1976 in New York I had read the book La Chute Finale by the French demographer Emmanuel Todd, predicting the collapse of the Soviet Union as a result of worsening economic problems, discrepancies between the Russian heartland and the vassal states, etc. – and I had written a commentary about it (under a pseudonym) that appeared in our paper The News World in early 1977. (I still have a clipping of that commentary, one of the first pieces I wrote that appeared in print).

2012/06/17

On God … and death …

I believe God, this one spirit or universal consciousness has basically divided itself into innumerable small parts by bringing about (in whatever way) what we regard as the physical universe with all the individual consciousnesses within it, each tied to a body of some kind or another.

We are really all one ― each one of us living beings and inanimate things is a part of this God ― but through our bodies we have the illusion of being separate from one another. When the bodies of us living beings fall away we return to where we came from and become one again completely with God ― the universal spirit. It is only the short-lived body of ours which makes us feel separate.

I cannot think of another way in which the world could be “just.” No concept of heaven and hell and good and evil that I have known would ever satisfy my sense of justice. For years I thought Sun Myung Moon’s Divine Principle had the answers but I have concluded that it doesn’t. It is no better than some other ideas that do not satisfy me at all.

God is absolutely responsible for everything that happens in the universe — from the greatest, most beautiful thing or event to the most horrible monstrosity or atrocity — but we all share that responsibility because we are all part of God. God as a whole has thrived on the differences and divisions among us that lead to conflict — especially in us humans, the spearheads of the evolution of his consciousness in this world — and on both the good and the evil things we have been doing to each other in our bodies, which make us feel separate. But his/our consciousness is evolving. God is learning with us, through us.

In our primitive days, when we were totally unable to understand the reality of our ultimate oneness, God gave us myths including the Bible and all the scriptures, which were propagated by people inspired by “Him” (or “Her,” “It”) to awe us and make us fear, and to herd us together as groups and make us fight each other for his own pleasure. To explain this: I believe the deepest parts of our nature are the emotions, which we share with God, our source. Yes, I believe God has the same emotions, though from a universal perspective, since his “body” is the entire universe.

Now, I think, the time may be coming when those myths are no longer useful. It is time that we humans outgrow them and look for the truth behind and beyond them. Most of all I hope we can truly become aware of the reality of our original and ultimate oneness.

On Life After Death

I have thought about the concept of a spirit world. Do I believe there is a world of spirit where we/our souls go after we die? Do I believe we have a spiritual body in which our soul/spirit resides for eternity and which resembles our physical body as it is when we are young and healthy? — No, I do not believe this! — This does not mean that I believe it is impossible.

I think that when we die – when our physical body dies and decays – our spirit dissolves in the ocean of universal consciousness, which is what God is to me. However, there remains a residue of a memory within God – a memory of us as we were when we were alive. As I have written before, I believe time – the “flow” of time – is really an accumulation of memory or memories within God. It expands ad infinitum, which is probably also why our universe seems to expand.

When we die, then, the memory of our life remains as part of this ever-growing universal memory. In this way we will continue to exist – but we cannot create new things or learn or grow because we will no longer be conscious as a separate entity. We will be fully assimilated or merged into the whole whence we came, a grain of salt dissolved in the ocean – still salt and still contributing our specific flavor to the ocean – at least to the tiny part of it that we have been able to influence during our lives – but no longer a separate entity and no longer able to expand our influence.

I may be wrong, of course, but it would be very hard if not impossible for me to return to a belief in a spirit world like that described by Unificationists and others such as Swedenborg.

2010/07/11

The Biggest Lie

We have been cheated, in a way. We have been living with a big lie: God [see my post below: My View of God as it has evolved -including the comments – and others about God further down.] But we have willingly participated. The lie is our lie, too. We have been happy to be deceived by God, because it is comforting to believe in a great supernatural power that is on the “good” side – which is always our side, because no one believes they are bad. Even the worst criminals and mass murderers believe they are “good.” They may admit mistakes – like most everybody does – but they always believe they are fundamentally “good.” However, the “good” can really exist only if there is also an opposing “evil.” We do believe in an “evil” but it is always someone else – just like God wants us to see “evil” as something entirely separate from him.

Yes, we are all part of this deception or self-deception. We participate willingly, most of the time. – But then we cannot separate from this God and his deception. This God leaves us some breathing space, some room for maneuver, some space for us to think for ourselves, because he wants us to grow, to improve, and he grows with us, improves with us – through us.

We are, all of us humans without exception, part of this God. We are really, ultimately, one. The whole cosmos is one, but we and any other intelligent beings that may exist are the most important elements of this one. The one, as I have said again and again, grows with us and through us.

I think perhaps the Buddhists have the deepest understanding of this oneness, this monism, this interdependence. The accounts of Buddhists I have read – such as those of the French Buddhist monk Matthieu Ricard – give me the impression that they have a much better and clearer understanding of the importance of oneness and interdependence than any Christians I have met, including the Moonies. Moon’s (Korean Moon Sun Myung of the Unification Movement/Church –see posts on religion below) teaching has many good points, for sure, but I regard it as deficient in the sense of explaining the real God, and misleading. I think Moon himself does not want to acknowledge the fact that God has deceived us by making us believe in an “evil” that is not of him. Moon’s interests are better served if he just ignores this – and I tend to believe he knows that very well. This would be the element of hypocrisy in Moon that I feel has been touched on indirectly by Nansook Hong, the ex-wife of his now-late son Hyo Jin.

Of course, it is clear that – ultimately – we will have to work with God, no matter how much he has deceived us. We are inalienable parts of him and he is totally in each one of us. We are really one. My contention is only that we have to grow up to be aware of the reality of God – not the fantasy we have believed in for so long. – And the reason we have to grow up this way – with this understanding – is that it is the only way God can continue to evolve – and, indeed, grow himself. As I have insisted many times before: God evolves through us (and any other beings at the highest levels of consciousness) – he grows through us…

2010/07/10

A dangerous bus ride on Pakistan’s Karakoram Highway -January 1988

Karakoram Highway January 1988

[from my article in the Middle East Times weekly, based in Cyprus.

・ My editor insisted that I use a somewhat impersonal style in this article

・ and did not allow me to write it up as a personal experience, which,

of course, it was. I wrote this after returning to Islamabad from a two-week trip to Baltistan in January 1988. This is the unedited version]

ISLAMABAD — In the winter, when the weather is bad in the mountains, taking a bus on Pakistan’s perilous Karakoram Highway (KKH) can be every bit as exciting as a game of Russian Roulette.

There is nothing like a rough ride of four and a half hours on the back of a four—wheel-drive pickup truck on a bitterly cold winter morning for the traveller to appreciate the awe-inspiring grandeur and desolation of the Karakoram mountain range, which contains the greatest concentration of high peaks anywhere and is regarded by geologists as one of the most unstable but also most fascinating features on the earth’s surface.

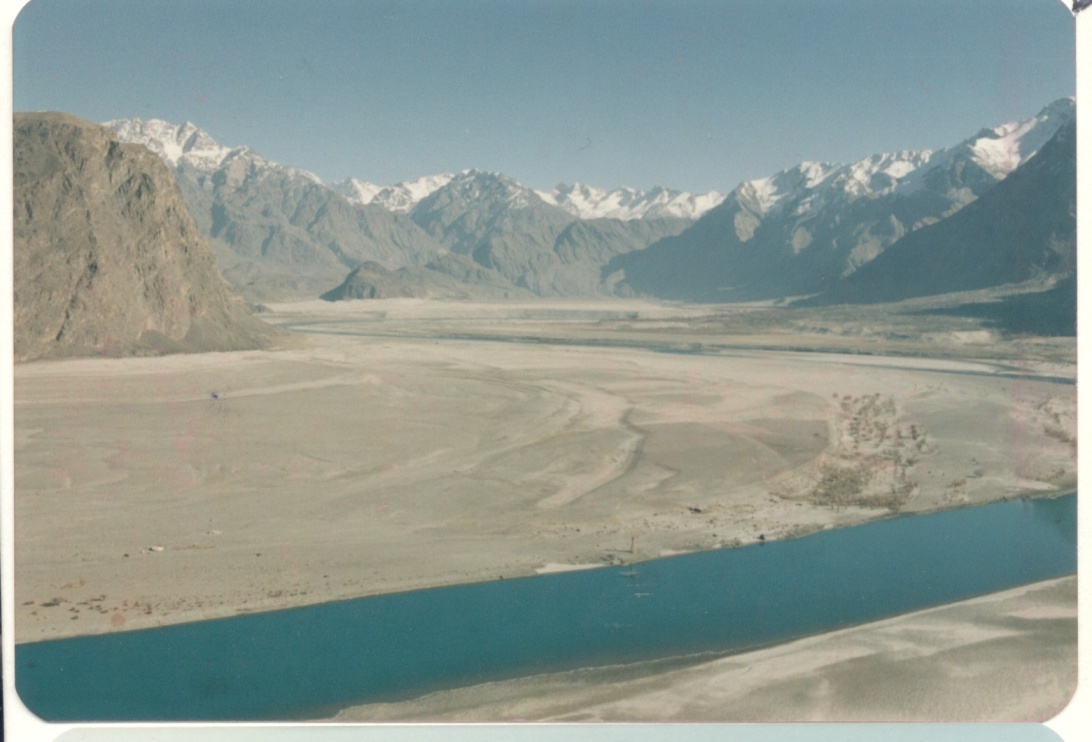

Along the 100-kilometre dirt road through the wild gorges of the Shyok and Indus rivers from Khaplu to Skardu in Baltistan one cannot help feeling that the enormous bleak rock faces, the jagged, snow-covered peaks poking into the clouds, the eerily frozen waterfalls, the huge boulders strewn all around and the vast scree slopes must belong to some distant uninhabitable planet but not to this earth. All of this spells danger. Under a gloomy, leaden sky, with the sun’s rays unable to break through thick clouds that hide the high mountain tops, there appears to be a veiled threat of impending disaster.

From Skardu, a small town in a wide, sand-covered valley at 2,300 metres, the road continues along the Indus River through dangerous gorges for about 500 kilometres before turning east away from the river on its way to Rawalpindi. If one travels on a public bus, this trip on the KKH has to be made in two stages. It involves a seven-hour journey from Skardu to Gilgit followed by a gruelling sixteen-hour trip to Rawalpindi on a different bus.

For four days from the end of 1987 until the first day of 1988 heavy clouds hung above Skardu Valley and hid the many 5,000-metre mountain peaks surrounding it on all sides. As the small airport in the valley had no radar, all flights were cancelled. The sky looked as though there was worse weather to come, so it seemed that there was no choice but to court disaster and take the bus.

Everyone in the packed, gaily-painted bus appeared to be in good mood when the journey began on the first day of the new year. The gloomy atmosphere outside did not affect the passengers for a long time as the bus sped on the asphalt road to the western end of the valley, then moved slowly over a narrow suspension bridge across the Indus and entered the gorge.

Compared with the bleakness of the grey, brown and black tones of the massive rock formations on its sides, the river was a pleasant sparkling green colour — almost inviting save for the fact that it was at times separated from the road by several hundred metres of sheer cliffs [I had already traveled the Karakoram Highway from Skardu to Gilgit and Passu in Hunza, and down to Rawalpindi 2 years earlier in August 1985 — but in summer the Indus is a dirty brownish color; quite different from its look in winter].

For most of the way the road appeared in good condition except for only one or two spots where part of its foundation had collapsed and plunged down the precipice into the Indus far below, leaving a gaping hole. The driver was quite agile and avoided such death traps easily. At least two small bridges spanning gaping chasms above raging tributaries of the Indus appeared rather dilapidated. The driver accelerated, apparently anxious to cross the bridges before they collapsed.

Some eighty kilometres before Gilgit a number of boulders the size of large cars had broken off from a gigantic rock formation that hung threateningly above the road. The road was hopelessly blocked. A maintenance crew was already at work preparing the area for blasting.

A little farther west, high above the road on a steep scree slope that seemed to stretch endlessly into the sky, two local shepherds herded their sheep and goats down as quickly as they could. The workers had signalled to them to come down because the blasting might make the scree come alive and cause a huge landslide. The shepherds wore roughly cut pieces of goatskin wrapped around their feet and ankles in lieu of shoes. They could perfectly well have fit into a Stone Age setting, with nothing on their bodies to show that they lived in the 20th century.

Luckily for the travellers, the three heavy blasts that were required to break up the boulders did not bring down any more rocks although cracks appeared in some huge slabs that hung precariously above the road. A lone bulldozer took more than two hours to push the debris over the edge into the Indus. Darkness fell soon after the road was cleared.

The bulldozer then headed west on the narrow road at a snail’s pace, and the bus driver had no choice but to follow at the same speed for some time. The driver quickly became irritated. He tried to pass the bulldozer several times but there was not enough space.

A military officer ran up on the road from behind the bus and knocked on the driver’s side window. The two exchanged some angry words. The driver had been ordered to pull the bus up to the edge of the precipice to allow a military truck to pass. He did so but complained bitterly. Then the officer also ordered the bulldozer to get out of the way at the next spot where this was possible.

The military truck sped on ahead, followed quickly by the bus, whose driver appeared very angry and nervous all of a sudden. He was determined to pass the military truck, which was already moving quite fast on this perilous road with rock walls or scree slopes to the right and a gaping black chasm to the left where in many places parts of the asphalt had broken off and plunged down into the gorge. The bus driver used his ear-shattering horn and flashed his lights wildly to drive his message home to the soldiers.

Finally, they let him pass. But they stayed close behind and flashed their lights as well, irritating the bus driver even more. His antics behind the steering wheel became increasingly wild and on several occasions the bus very nearly went over the edge of the cliff. Two passengers sitting in the front abreast of the driver angrily warned him to slow down. Others anxiously mumbled prayers. The angry warnings seemed to madden the driver even more, and some other passengers urged everyone to calm down. The atmosphere in the bus became increasingly tense, laden with a strange mixture of anger and naked fear.

Suddenly, there was another bus in front and the angry driver of the first bus flashed his lights to signal that he wanted to pass. The bus in front slowed down but stayed in the middle of the road for some time. When it finally allowed the first bus to pass its driver was fuming. To make matters still worse, the other bus also stayed close behind and flashed its lights. Many passengers on the first bus were terrified but no one dared to approach the driver for fear of distracting him in this extremely dangerous situation.

After what appeared to be an eternity, the valley widened and the bus stopped at a petrol station. When the bus left the station after refuelling, a teenage boy sat down on an improvised seat next to the driver and this seemed to calm the man down. Later, he let the boy drive the rest of the way to Gilgit. Although the boy’s driving was somewhat unsteady from lack of experience, the passengers were relieved that the bus was now moving more slowly and carefully.

Next morning, another bus with a few foreigners among the many passengers left Gilgit on the long journey to Rawalpindi. The driver was a man of about 50, clearly very experienced and skilful. But on this trip the road was in very bad condition — and the weather turned worse.

There were scores of spots on the way where rocks of all sizes had fallen from above and very nearly blocked the road. Often the space left between the bigger boulders and the edge of the precipice was just barely wide enough to allow the bus to pass.

Again and again, the bus lurched sideways as it moved slowly over very uneven terrain past big boulders. Some terrified passengers, who saw the gaping abyss come up from below their windows as the heavy vehicle seemed close to the point of rolling over, leaned into the aisle and looked the other way.

At one point, some rocks rolled away from under the wheels of the bus at the edge of the broken road and the driver had to quickly steer the vehicle towards a big pile of boulders away from the precipice. The boulders tore into the side of the bus, causing minor damage, but passengers later congratulated the driver on his presence of mind.

After a seemingly endless series of similar incidents, the passengers felt relieved when the bus crossed a bridge on the Indus, hoping that the worst was over. But then, shortly before dark, it began to rain.

Water is both a boon and a bane in the mountains. Local villagers need it for drinking, cooking, washing and irrigation but it also inevitably brings down boulders and mud, and it causes the landslides that so often obstruct the KKH.

The bus drove on into the night on the wet road, dodging many more fresh rockfalls. In one area, the going was slow over a stretch of at least 20 kilometres where many landslides had completely blocked the KKH for over two weeks in October. The road was still badly scarred and the piles of debris on one side did not allow two vehicles to pass each other along most of this stretch.

After the bus finally crossed the last bridge over the Indus and headed out of the gorge, the driver stepped on the accelerator. As the road was still dangerous, some passengers became concerned that the bus was moving too fast. An Australian woman expressed her worries to a Pakistani passenger who translated for the driver.

After more than 12 hours on the KKH the driver was clearly becoming tired and it seemed that he was accelerating because he was afraid to fall asleep. There were a few more hair-raising moments when the driver nearly seemed to lose control of the bus in dangerous curves. But he finally stopped and allowed a younger colleague to drive the rest of the way to Rawalpindi.

It is by braving such a danger-filled winter journey on the KKH that one can learn to appreciate the remarkable feat that the building of this road represented. One can also easily understand how the KKH claimed at least 500 lives during the 20-odd years of its construction and many hundreds more in the last eight years since it was opened.

My last trip into Soviet-occupied Afghanistan in October 1987

asadab.DO [For information: This was originally written on a small NEC PC-8201 laptop with less than 32 kilobytes of usable RAM. This is scanned from a printout of the original, unedited version that I typed up in Peshawar]

ASADABAD — KUNAR PROVINCE (18-22 October 1987 — written on 1 November) [1987 in Peshawar, Pakistan]

[from my article in the Middle East Times weekly, based in Cyprus]

TARI SAR PLATEAU, Afghanistan — Mujaheddin commander Ajab Khan, a short, wiry man with a vaguely bird-like quality in his movements and speech, is perched precariously on a rocky outcrop. In rapid Pakhtu, he is speaking into the microphone of a red plastic walkie-talkie. Next to him, Pazlimalek, a tall, seasoned fighter at 25 with a thick beard, leans on a flat rock and peers through binoculars into the Kunar Valley far below.

Seconds earlier, the heavy blast of the driving charge of an 82-millimetre mortar reverberated through the rugged mountains and valleys to the east of the fast-flowing, slate-grey Kunar River. Then a small cloud rose from some low hills across the river, just above Shigal Tarna, a garrison of a few hundred government troops.

“Down five millièmes,” suggests Pazlimalek, and the commander repeats the message into his microphone. The next mortar bomb, fired by one of two mujaheddin positions in the mountains near the border with Pakistan, explodes on the road that leads to the base of the Soviet-backed dushman, the enemy. The second mortar also places a bomb close to the road.